Empire State Plaza Microgrid Vies for NY Prize

Eric Olson | July 11, 2017 An aerial view of Empire State Plaza. Credit: Wikipedia

An aerial view of Empire State Plaza. Credit: Wikipedia

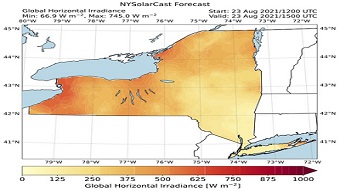

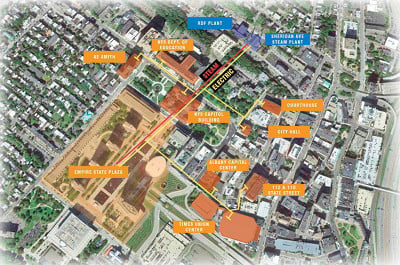

Map of the facilities served by the proposed Empire State Plaza microgrid project in downtown Albany. (Click to enlarge.) Image credit: Cogen Power Technologies

Map of the facilities served by the proposed Empire State Plaza microgrid project in downtown Albany. (Click to enlarge.) Image credit: Cogen Power Technologies

Part 1 of this series delivered a brief overview of microgrids and their benefits and looked at the NY Prize Competition administered by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). Part 2 will look at one NY Prize competitor in particular: the Empire State Plaza microgrid project in the state's capital, Albany.

Out of nearly 150 communities that applied for Stage 1 of the three-stage competition, the project was one of 83 that won $100,000 in funding for a feasibility study in July 2015. It was then awarded $1 million as one of 11 Stage 2 winners in April 2017 to conduct detailed technical, financial and commercial assessments of the project.

The Empire State Plaza microgrid would serve a diverse customer set, including a large arena, office complexes and various small buildings. The facilities served could include the Empire State Plaza (ESP), the Alfred E. Smith Building, the New York State Capitol Building, the New York State Department of Education, the Times Union Center, the Albany Capital Center, the New York State Comptroller’s Office (110 State Street), an Albany County office building (112 State Street), City Hall, the Albany County Courthouse and the Sheridan Avenue Steam Plant (SASP).

Combined Heat and Power

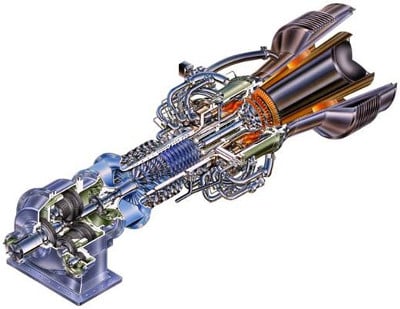

A combined heat and power (CHP) plant would serve as the distributed energy resource in the Empire State Plaza microgrid. The CHP would be powered by two dual-fuel Solar Taurus 70 gas turbine generators (GTGs) with an average output of 16 MW. The GTGs would normally be fueled by natural gas, but would be capable of running off of No. 2 fuel oil as well.

A Solar Taurus 70 gas turbine generator. Image credit: Solar Turbines IncorporatedExhaust gases from the GTGs would be recycled by two heat recovery steam generators (HRSGs) to generate 65,600 lb/hr of steam at 250 psig and 450° F. The HRSGs would be equipped with gas-fired duct burners to boost their combined steam generation capability to 140,000 lb/hr. That figure falls short of the average steam demand of the Empire State Plaza during the winter of 160,000 lb/hr. To fill the gap, the existing SASP steam plant would continue to produce steam. This would be particularly important during potential periods of natural gas curtailment because the SASP boilers fire fuel oil, which the HRSGs are not capable of.

A Solar Taurus 70 gas turbine generator. Image credit: Solar Turbines IncorporatedExhaust gases from the GTGs would be recycled by two heat recovery steam generators (HRSGs) to generate 65,600 lb/hr of steam at 250 psig and 450° F. The HRSGs would be equipped with gas-fired duct burners to boost their combined steam generation capability to 140,000 lb/hr. That figure falls short of the average steam demand of the Empire State Plaza during the winter of 160,000 lb/hr. To fill the gap, the existing SASP steam plant would continue to produce steam. This would be particularly important during potential periods of natural gas curtailment because the SASP boilers fire fuel oil, which the HRSGs are not capable of.

Compared to separate heat and electricity production, the CHP plant’s cogeneration of thermal and electrical energy would improve energy efficiency. The project would save 25,642 tons per year of CO2 equivalent and reduce energy spending by an estimated $4.5 million for the microgrid’s participants.

Control and Recovery

A plant control system (PCS) would provide supervisory control and monitoring of the CHP equipment and a load management system (LMS). The LMS, a custom logic controller-based automated system, would monitor power sources and loads in the microgrid. In the event of demand exceeding supply, such as a utility outage, the LMS would carry out an automated load shedding process with a response time of 38 milliseconds or less.

The CHP plant would have a black start capability to restore power in the event that both GTGs were down and power from the grid was not available. A 1 MW backup diesel generator would be available to provide the power required to start up one of the GTGs, which would provide the necessary loads to start the second GTG. Black start support to the main utility grid could then be provided as an ancillary service.

In the event of a natural disaster or utility outage, the microgrid would provide power to critical facilities that could serve as a place of refuge for community members. The Empire State Plaza, Times Union Center, and the Albany Capital Center combined could provide shelter for 30,500 people, or 31 percent of the city of Albany’s population of 98,566.

Utility Involvement

Although the microgrid could enter island mode to provide isolated local power in the event of a disaster, most of the time it would be connected to the traditional grid.

“While microgrids can stand on their own during grid outages, they need to be coordinated and operating with the grid when both are running together,” said John Saintcross, Assistant Director, NY Prize at NYSERDA. As operator of the Empire State Plaza microgrid CHP plant, the Office of General Services (OGS) would need to work with the local utility provider— National Grid — to ensure its smooth integration with the grid. The microgrid’s voltage and frequency would be controlled by the utility when connected to the grid.

The Sheridan Avenue Steam Plant (right) and adjacent decommissioned Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) building. The RDF ceased operations in 2012 and will be the future site of the new CHP plant.

The Sheridan Avenue Steam Plant (right) and adjacent decommissioned Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) building. The RDF ceased operations in 2012 and will be the future site of the new CHP plant.

OGS and the Department of Public Service (DPS) would collaborate with National Grid on formulating and testing systems and processes for how the utility could become a microgrid platform provider, a unique learning opportunity.

In addition, cooperation between OGS and National Grid would be needed for the lease or sale of existing utility infrastructure, the permitting of rights of way across a public road and the combination of multiple electricity customers into a single client through the Empire State Plaza.

With the microgrid forecasted to generate over 80 percent of the electricity needed to power its ten facilities, National Grid would lose 15 MW of demand. There would be potential, however, for the utility company to gain new revenue streams from the project. These could include: fees for buying or leasing the existing medium voltage switch and step-down transformers at each facility’s substation; service fees as the provider of metering and billing services for the microgrid’s customers; and charges for the natural gas needed to power the CHP plant.

Low-cost financing for the project would be provided by the New York Power Authority (NYPA), improving its economic viability and return on investment. Regardless of the full multi-facility microgrid proposal’s results in the competition, the base CHP project powering only Empire State Plaza is expected to move forward because it would achieve a positive internal rate of return even without the additional funding provided by the NY Prize. If selected as a winner of the competition, the project would expand the microgrid to the additional ten facilities, enabling the CHP plant to operate closer to full load and peak efficiency.

Successful completion of the project would help establish microgrid operational effectiveness and demonstrate the technical, business and regulatory feasibility of the technology, a major goal of the NY Prize Competition.