Old Tech, New Think: The LiquidPiston Rotary Engine

Robert Springer | July 07, 2015Despite a 100-year-plus history, traditional internal combustion engines are inefficient, converting about 20% of fuel energy into useful work.

LiquidPiston, a Bloomfield, Conn.-based startup, believes that their rotary engine can eventually approach 50% efficiency. The X Mini, about the size of an iPhone, is quiet, virtually vibration free and could be on the market in another two to three years.

Founder and chief technology officer (CTO) Dr. Nikolay Shkolnik and his son Alexander Shkolnik, the firm’s joint co-founder, founded LiquidPiston in 2004 after their engine idea won second place in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology $50,000 Entrepreneurship Competition.

The LiquidPiston team started out having limited knowledge about engines but an extensive knowledge about physics and robotics. (Nikolay’s has a PhD in physics and Alex PhD is in robotics and artificial intelligence.)

Good News, Bad News

“On the one hand, the benefit of the team is they knew nothing about engines,” says William A. Frezza, a former venture capitalist who volunteered to coach the team and invested in the company in 2007, later joining its board. The team had never built or shipped an engine, and their naivety allowed them to attack problems without being burdened by 100 years of tradition. That’s the good news.

The bad news is they know nothing about engines, Frezza says. “They had never shipped an engine before, and they didn’t know about 100 years of painful lessons it takes to get an engine to market. This is the nature of technology leaps.”

LiquidPiston co-founders Nikolay and Alex Shkolnik display their X1 Mini engine, a new take on the rotary engine. Image source: LiquidPistonThe father and son team focused on developing a new thermodynamic cycle.

LiquidPiston co-founders Nikolay and Alex Shkolnik display their X1 Mini engine, a new take on the rotary engine. Image source: LiquidPistonThe father and son team focused on developing a new thermodynamic cycle.

“It really started with the physics, how to improve the engine, and the engine itself came secondary to the physics,” Alex says. “So we’ve developed a number of different engines that can theoretically implement our high efficiency hybrid cycle, the ‘HEHC’ cycle.”

The engine has two moving parts – a rotor and a shaft – and “behaves like a three-cylinder, four-stroke engine which operates on our new cycle,” Alex says.

The company has some long odds to overcome to bring the engine to market, says Michael Andrie, Researcher at the University of Wisconsin’s Engine Research Center and Program Director for Professional Development. “So far, Curtiss-Wright, Wankel, Mazda and other people that have worked on the engine have not been able to make it work as well,” he says. “There are some new materials that they can use. Maybe they’ve found one that works well.”

A New Type of Rotary Engine

A visit from a Honda engineer convinced the young startup that their engine design might be something special —– if they could properly seal it.

“They sent a very knowledgeable guy out, and what he said is it’s all about the seals,” Frezza says. “If you can seal this thing, you will change the world.”

Without accurate sealing, engines lack a good compression ratio, are inefficient and have emission problems. Frezza says that an engine expert from Harvard University told him, “’There’s no such things as engines. There’s just seals.’ He was right, and credit to the team for some out-of-the-box thinking on the seals.”

It took the LiquidPiston team several years to solve the seal problem. Alex says sealing the inverted Wankel engine was much easier than on a traditional Wankel. “Our apex seals are stationary, which makes them easier to lubricate. We have never seen ‘chatter’ which is common for Wankel rotary engine development.”

The company used funding from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to optimize the seal design. “We did a lot of testing to optimize the seal tribology – understanding what block temperature is okay, and what seal material and coatings work well together,” Alex says.

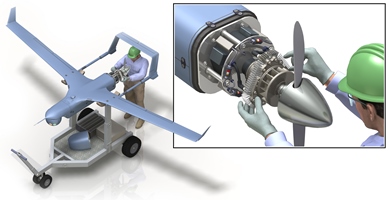

Artists rendering of a technician checking a LiquidPiston rotary engine on a drone aircraft. Image source LiquidPiston. The X Mini has three combustions per revolution of the motor, which makes it a smooth operating engine, according to Alex. “There are no off-weighting masses,” he says. “We don’t have a piston moving back and forth, so you don’t get the vibrations of a piston engine. It’s quieter and we actually run the engine with no muffler in the lab.”

Artists rendering of a technician checking a LiquidPiston rotary engine on a drone aircraft. Image source LiquidPiston. The X Mini has three combustions per revolution of the motor, which makes it a smooth operating engine, according to Alex. “There are no off-weighting masses,” he says. “We don’t have a piston moving back and forth, so you don’t get the vibrations of a piston engine. It’s quieter and we actually run the engine with no muffler in the lab.”

“One of the key advantages of our cycle is we’re going after a high compression ratio, but we’re also constraining the combustion so that it is closer to a constant volume combustion process, and so we’re getting the efficiencies of both cycles simultaneously.”

Constraining the combustion should allow a 40-horsepower LiquidPiston engine to be 50% efficient over the drive cycle, Alex says.

Scalable Power

With a scalability of 1 to 1,000 horsepower, there doesn’t seem to be a limit to where manufacturers will be able to use a LiquidPiston engine. Portable generators and the automotive industry are two possible fits, and Alec says that the company is in discussions with helicopter manufacturers.

The company shouldn’t have a problem scaling the engine, according to Andrie. “There’s nothing that keeps you from scaling it,” he says. “It’s just like reciprocating engines, right? They can add extra rotors just like you add extra pistons, go to bigger rotors, and all that scales.”

Lawn and Garden

Despite the potential of larger engine markets, the company’s initial targets will be the lawn and garden power tools and the small generator space, Alex says. Those markets have lower barriers to entry as durability and emissions requirements are not as stringent as in the automotive space.

The company hasn’t yet determined the emission characteristics of the engine, says Alex. He says he expects that as the engine efficiency continues to increase emissions will be in line, or better than, conventional piston engine emissions.

Efficiency is not as critical for handheld lawn and garden equipment. Low vibration, low noise and high power density are key selling points. Andrie agrees, saying that fuel efficiency isn’t as important in the small engine space. But cost is, he says, as players in the market will “jump through unbelievable hoops to save a penny.”

“As a startup company we have to be selective in how we’re approaching the market, but really in the longer term we can hope to be in any of the engine markets,” Alex says. He says he thinks the X Mini could be less expensive than a comparable power piston engine, and “certainly cheaper than a four-stroke and maybe in the ballpark of a two-stroke” engine.

LiquidPiston recently entered into a $1 million agreement with DARPA to “demonstrate the feasibility of doing a high efficiency diesel engine,” Alex says. In this pilot study, the company will modify its X Mini engine to run on diesel fuel.

“The next step, if the Army or DARPA decides to carry the program forward, it would be a full diesel engine program to develop an actual diesel engine,” Alex says.

Generators are a natural application for the engine, he says. “If you look at a 3 kilowatt generator set, it weighs close to 400 pounds,” he says. Imagine, if an engine existed for that generator that is the size of a grapefruit and weighs 30 pounds. “That’s a game-changing technology for the military for mobile power applications or wherever you need power in the field where they would use generators such as unmanned aircrafts, small drones, mopeds, and vehicles.”

Andrie is realistic about the company’s prospects. “I would love to see them successful,” he says, then cautions, “history says that there are some issues that they’re going to have to deal with.”

To contact the author of this article, email engineering360editors@ihs.com