Researchers Using eDNA to Detect the Presence of Great White Sharks in Local Waters

Marie Donlon | September 17, 2018 Environmental DNA collection and sequencing can detect the general presence of white sharks. Source: Chris JerdeFollowing news that a swimmer had died after being attacked by a shark off the coast of Massachusetts last week, a team of researchers is investigating ways to sound an alarm that sharks, particularly great whites, are swimming in the same waters as beachgoers.

Environmental DNA collection and sequencing can detect the general presence of white sharks. Source: Chris JerdeFollowing news that a swimmer had died after being attacked by a shark off the coast of Massachusetts last week, a team of researchers is investigating ways to sound an alarm that sharks, particularly great whites, are swimming in the same waters as beachgoers.

Researchers from UC Santa Barbara, the U.S. Geological Survey, California State University Long Beach and Central Michigan University (CMU) have worked together on an early detection system that relies on environmental DNA (eDNA).

"One of the goals of this research is for a lifeguard to be able to walk down to the shore, scoop up some water, shake it and see if white sharks are around," said Kevin Lafferty, a USGS ecologist and researcher with UCSB's Marine Science Institute (MSI). Lafferty is lead author of the paper "Detecting southern California's white sharks with environmental DNA," published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

According to researchers, a resurgence in great white shark populations is occurring thanks to the success of federal and state protections concerning fishing and the recovery of marine mammal populations.

"However, white shark population recovery has co-occurred during a period when more people than ever before are using the coastal ocean for recreation, ultimately increasing the likelihood of interactions," Lafferty said. "While sightings of juvenile white sharks have risen considerably along California over the last eight years, there has been no dramatic increase in shark bites on people."

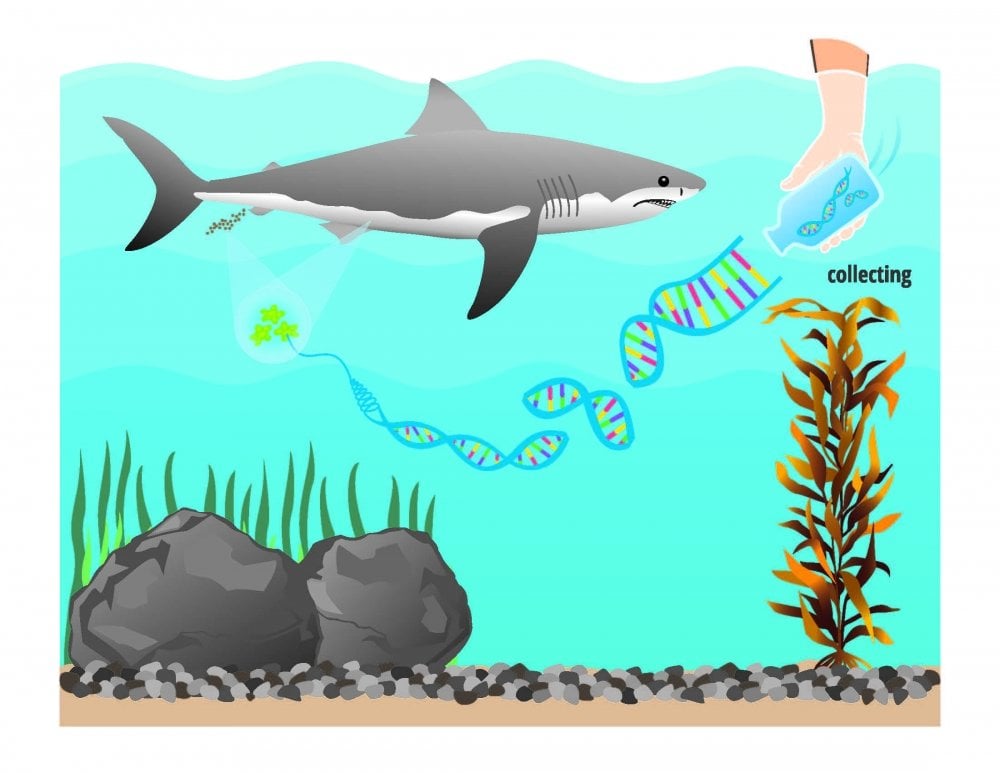

Analyzing eDNA, which is genetic material such as feces, mucus or shed skin containing an animals’ genetic signature left behind in the animal's environment, researchers can determine if a shark is nearby. It is this genetic signature that researchers can parse and identify through genetic sequencing. Extracting and amplifying specific genes in the DNA fragments discovered in water samples, researchers can match the DNA in those samples to specific species using a new protocol.

"Ten years ago we started working on eDNA," said eDNA expert and MSI researcher Chris Jerde, who is a co-author of the paper. "The advances in technology since then have dramatically improved the reliability, portability and widespread application of the method."

The new method, which is a species-specific genetic analysis called digital droplet PCR, allowed researchers to design genetic markers from white shark tissue. Then, the team analyzed water samples taken from areas near the shark aggregation and samples a mile away from shark aggregation. Samples from areas located near shark aggregation matched the white shark tissue genes while water samples taken from a mile away did not match, suggesting that the water sample could be used to detect white sharks.

Yet, because eDNA will likely drift with currents and because sharks can swim significant distances in the time it would take for eDNA to disperse, the method for detecting the presence of a white shark only gives a rough idea about where the sharks might be at an exact moment.

While it is generally accepted that most shark bites are inflicted due to curiosity, mistaken identity or defensiveness, researchers believe that lifeguards monitoring eDNA would allow swimmers, surfers and beachgoers to be extra vigilant.

"We can now sample eDNA along the coast to make better maps and seasons for white sharks," Lafferty said. "And if we can do it for white sharks, we can do it for other marine species, too."

Added CSULB professor, white shark expert and study co-author Chris Lowe, "We can use eDNA not only to determine whether white sharks have been present at a beach, but also to determine if their favorite food is there as well, such as stingrays. Once we are able to better refine and calibrate the methods, another goal will be to integrate eDNA technology into autonomous surface vehicles that can be programmed to move along the coast sampling water and send data into the cloud, along with text alerts to local lifeguards, of the presence of white sharks at a particular location. This technology holds great promise for future, near real-time monitoring."

"New advances in eDNA are allowing for not just a single species to be detected, but instead the DNA for the water sample is screened for all fish species or all amphibian species," Jerde said. "The same technology used to decode the human genome is now used to sequence all the DNA in a water sample. From this we can monitor fish stocks, measure the presence or absence of rare species, and better connect how climate change and pollution are impacting biodiversity."