Does Pollution Grow in Lockstep with Economic Growth?

David Wagman | September 21, 2017As an economy grows, so does pollution, but the two don’t move in lockstep, according to research from the St. Louis branch of the Federal Reserve Bank. A recent essay by bank economists suggests that pollution increases at a slower rate than economic growth.

Research Officer and Economist Guillaume Vandenbroucke and Research Associate Heting Zhu’s conclusion contrasts with an older hypothesis called the “environmental Kuznets curve” or EKC.

Research Officer and Economist Guillaume Vandenbroucke and Research Associate Heting Zhu’s conclusion contrasts with an older hypothesis called the “environmental Kuznets curve” or EKC.

The EKC variation holds that pollution increases with economic growth in the early stages of development. Beyond a certain level of development, however, the trend reverses, and economic growth improves environmental conditions by creating the resources to do so.

Vandenbroucke and Zhu noted that a 2004 paper found that pollution rises monotonically with economic activity. “A 1 percent increase in economic activity raises pollution but at a slower pace. That is, pollution is increasing more slowly than GDP,” Vandenbroucke and Zhu wrote.

Three Kinds of Pollution

In the essay, the authors looked at three kinds of pollution typically generated by economic growth:

- CO2 emissions

- Greenhouse gas emissions overall

- PM2.5 particulate matter emissions

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, CO2 emissions rose at an average annual rate of 0.4% between 1990 and 2014. Meanwhile, GDP per capita increased at an average annual rate of 1.4%.

“Thus, the average person in the United States has benefited from relatively ‘cleaner’ goods and services produced with fewer emissions of CO2,” the authors wrote.

Between 1990 and 2014, greenhouse gas emissions rose by 0.28 percent on an average annual basis, again lower than the 1.4 percent average annual increase in GDP per capita.

The authors noted that this pattern holds when the economy slows: Greenhouse gas emissions fell at an average annual rate of 1.2 percent from 2005 to 2011, or the period encompassing the Great Recession, while both GDP and population rose at an average annual rate of 0.9 percent.

“Thus, GDP per capita was stagnant, while total greenhouse gas emissions decreased,” the authors noted.

Vandenbroucke and Zhu then looked at particulate matter, in particular PM2.5, which measures the concentration of particles less than 2.5 micrometers in size in a given volume of air.

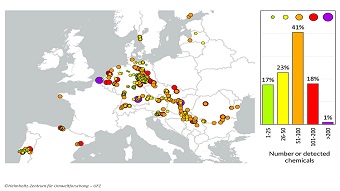

When looking at the relationship between PM2.5 and GDP per capita across countries from 1990 to 2015, Vandenbroucke and Zhu found a negative correlation. “In other words, one unit of GDP per capita can be produced with fewer particulate matter emissions in countries with high GDP per capita,” they wrote.

Pollutants and GDP

A nation’s economic growth can contribute to several different kinds of pollution, affecting health and motivating policymaking decisions.

“Our point is not to dispute the quantity of pollution, nor is it to argue about the effects of pollution on people’s health or the climate,” Vandenbroucke and Zhu said. “Instead, we suggest that the costs of pollution should be assessed relative to the benefit of said economic activity. If both economic activity and pollution are rising, one ought to ask whether the costs are rising faster than the benefit...or the opposite.”

In sum, “We find that pollution in the United States, measured by particulate matter or CO2 emissions, rises with economic activity, but at a noticeably slower pace,” they said.